“

Of all forms of inequality, inequality in health is the most inhumane

”

The Thin Line Between Location and Health Disparity

Provider Network Adequacy: The Gold Standard,

or Fool’s Gold?

When discussing network adequacy standards, it’s easy to get lost in the minutiae. On a larger scale, political and social belief systems can disrupt any meaningful discussion of this issue. At the payor level, we sometimes tiptoe around these issues due to competitive market conditions and regulatory headaches.

A Simple Measure of Time/Distance Isn’t So Simple

Scenario 1 -

Medicaid Managed Care Plan Participant:

“Mary is a 30-year-old woman living in a large metro area. She can’t afford a vehicle, so she relies on public transportation. She also cannot afford to take time off of work, since she can barely afford her rent.

One day, Mary catches the flu. According to CMS rules, she should have access to an in-network primary care physician within 10 miles (and 15 minutes) of her location. She looks online and find that although there are several PCPs closer to her, they are not participating with her health plan, so she chooses one that’s further away in order to avoid paying out-of-network rates.

Despite falling within the adequacy standards for the plan, the bus route she has to take actually makes the doctor’s office 14 miles away, and because there is always traffic on weekdays, it takes 45 minutes for her to reach the clinic. This means she will have to take more time off of work in order to get a prescription to take care of a common ailment.

Instead of taking care of herself, she decides she cannot afford to take that much time off of work to go to the doctor, which compromises her health.”

Scenario 2 -

Medicare Advantage Plan Participant:

“Grace is a 70-year-old immunocompromised woman from a rural area, and though she has a car, she needs someone to drive her into town, so she relies on her son. Grace also comes down with the flu.

Unfortunately, because there is a river between Grace and the nearest town, and although there is a non-participating clinic closer to her, she has to travel a significant distance to get to a bridge in order to cross and get to an in-network provider for care.

The Haversine model doesn’t adequately measure the distance to her nearest primary care physician, due to the unique geography of her rural area. The actual travel distance to the nearest primary care physician with coverage is 45 miles, and not 30 miles “as the crow flies”.

Grace’s son only gets off of work 60-minutes before the doctor’s office closes, which is not enough time for her to arrive before the office closes. Her only alternative in-network option is an expensive ER visit. Grace goes untreated, leaving her at risk of suffering adverse side effects and an avoidable hospital admission from the flu.”

In both scenarios, the payor meets adequacy standards, but the member’s access to care is inadequate.

The obvious (and oversimplified) solution to both of those scenarios is to adjust the adequacy model and recruit additional providers. If we can make sure that Mary and Grace have equal access to care based on their location and access to transportation, other, more complicated socio economic issues could have a far less significant impact on Mary and Grace’s health outcomes.

Geospatial Data, Advanced Analytics, and Old-school Algorithms

The aforementioned examples illustrate the limitations of legacy algorithms and historical adequacy standards. Those standards were a necessary, and important first step toward health equity in the U.S.

To achieve the desired outcome and the intent of our adequacy standards, meeting that time/distance requirement is a milestone along a path to building a great network. Not only do payors need to build more robust networks that deliver high quality, efficient care, they need to minimize the impacts of provider crowding and care deserts wherever possible.

Therefore, as a next step, a modern provider network should leverage geo-spatial computational models and data analytics to build dynamic, true-to-life time/distance data to work toward better standards for care availability.

Payors that move to the more advanced adequacy model stand to gain a significant competitive advantage, including demonstrating qualifications for state Medicaid/Medicare contracts. The very same technology that enables health equity can be utilized by payors to reduce the cost of care, optimize expenses, improve network performance, and reduce redundancies. It’s a winning strategy.

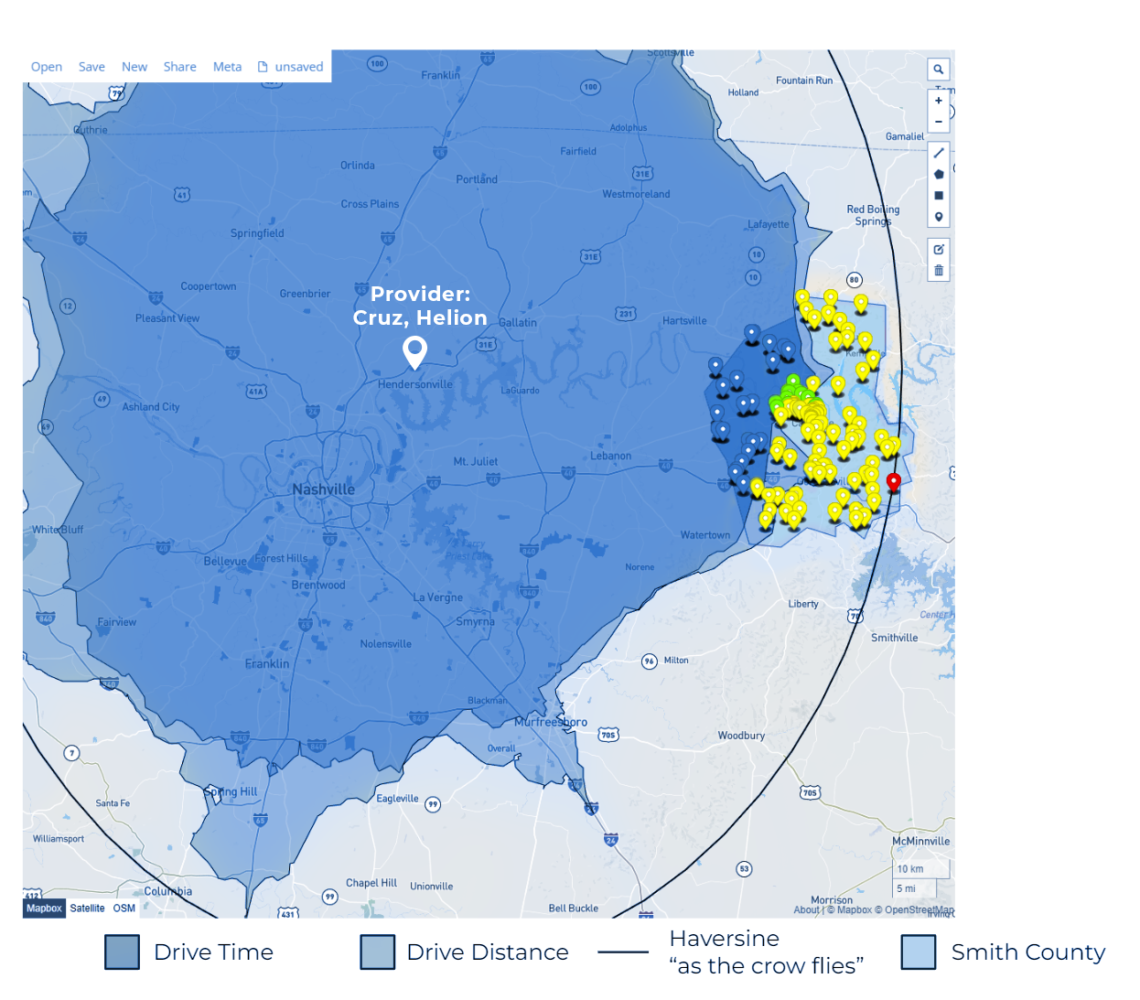

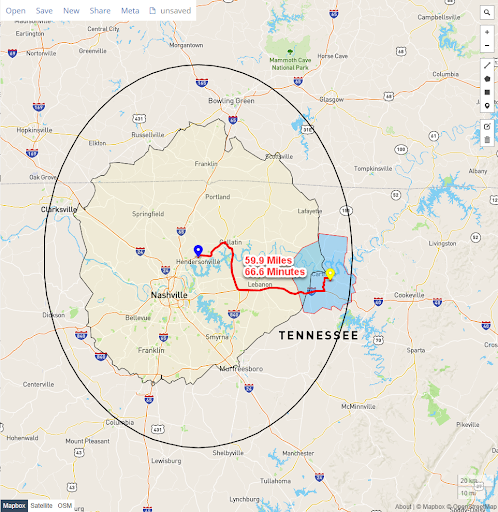

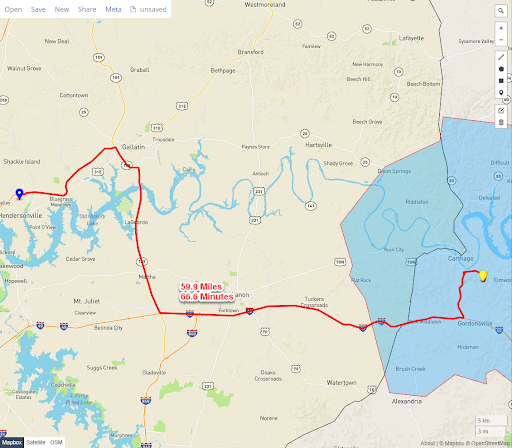

These two maps illustrate the difference between a more modern, cutting-edge, geospatial network adequacy model (like the one we’ve built into the andros platform) and the traditional Haversine model.

Patient Level Example

Actual distance and path a patient will have to travel to reach the provider

Yellow point is patient just outside of andros projected drive time for coverage

Red line represents the actual distance and driving time from beneficiary to the provider.

Drive crosses over the Cumberland River

Beneficiary is just outside the required travel time of 60 minutes and 45 miles

Where Do We Go From Here?

Of course, health equity doesn’t just benefit payors, it benefits everyone, everywhere. The goal of a provider network should be to provide quality care to the plan’s members. What we see as meeting CMS standards may not translate to access to quality care to the most vulnerable members of the communities and populations we intend to serve.

How do we better serve people and communities? How do we diminish health inequities and build a happier, healthier, and more productive society? Can we really track disparities across geographies, build robust and deep understandings of communities, and leverage data to create powerful healthcare solutions that fluidly move throughout the dynamism of health inequality if we aren’t even measuring geographic distances correctly?

When adequacy standards lead to inadequate availability of care, it can be challenging to build truly transformative provider networks. Targeted interventions — regulatory or not — should leverage the best technology available. Provider networks need to be built to serve the needs of the community, and we need to improve our regulatory requirements to address health equity.

Having access to quality care within a specific time and distance from you isn’t a specific racial, socioeconomic, or cultural right. It’s a human need. The shortcomings of our current standards for adequacy are threatening the effectiveness of health networks and the wellness of people across the United States. We can do better.